Ayudando Guardians Inc. opened its doors with two nurses and a medical records expert in 2004. It was formed, according to its website, “due to the enormous need for guardians and conservators in the State of New Mexico.”

The nonprofit Albuquerque-based guardian and conservator firm – now accused along with its principal owners of looting millions of dollars from client accounts – grew over the years.

And, the company increasingly became a family affair.

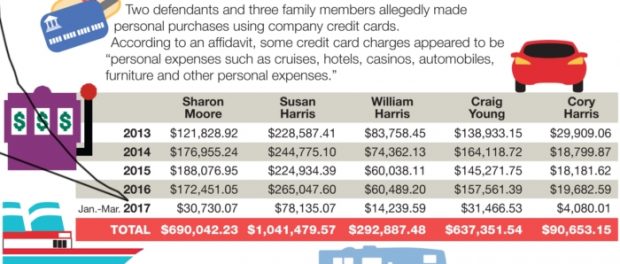

Two of the three family members serve on Ayudando’s board of directors, drawing salaries of at least $56,000 a year, a 2015 IRS tax form shows. Each of the three relatives racked up tens of thousands of dollars in credit card charges from 2013 to March 2017, one affidavit states.

The purchases “do not appear to be related to Ayudando clients,” said one affidavit stated. “The credit charges appear to be personal expenses such as cruises, hotels, casinos, automobiles, furniture and other personal expenses.”

The affidavits identify the three relatives as: Harris’ husband, William Harris, Craig Young and Cody Harris. They have not been charged.

Susan Harris and Moore were arrested after a 28-count federal criminal indictment was unsealed July 19. The company was also indicted.

Several Ayudando employees who became confidential witnesses in the case told investigators that Ayudando appeared to be putting “more and more family members” on the payroll and “the business owners and their families appear to be living lavish lifestyles with expensive vehicles and expensive vacations,” one affidavit states.

The organization was tightly run by the family insiders. Affidavits allege that some non-family employees had their access to client accounts cut off – meaning they lost their ability to monitor transactions and balances.

There was even a file room at the company’s Central Avenue offices that non-family members were barred from entering, an affidavit alleges.

Mission gone awry

Ayudando’s web site sets out a lofty mission statement.

“As a provider for the State of New Mexico,Veterans and private individuals, Ayudando employs an experienced team of licensed social workers and rehabilitation specialists.”

“This diverse group is able to assist our clients with their everyday needs as well as providing assistance in managing their financial needs.”

Details emerging from the yearlong federal investigation describe a different kind of operation.

Federal agents made detailed allegations in affidavits seeking search warrants to obtain company records and, more recently, sought permission to seize a 2018 K-Z RV Durango Gold 5th wheel RV purchased in late June of this year by Harris and her husband of 27 years, William Harris. They allegedly bought the RV using proceeds from an illegal scheme to embezzle funds from clients, some with special needs, according to an affidavit filed July 24.

Harris, 70, and Moore, 62, have pleaded not guilty to charges of money laundering, mail fraud, conspiracy and aggravated identity theft that allegedly dates back to 2006. Both women were ordered released from federal custody under certain conditions and after posting property bonds Friday.

Both have homes in the Tanoan Country Club area in Albuquerque’s Northeast Heights. An attorney for Moore didn’t return a Journal phone call. Robert Gorence, who represented Susan Harris at her detention hearing, had no comment. Efforts to reach lawyers who have represented the firm in the past were unsuccessful last week.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Albuquerque declined to comment on whether the family members named in the affidavits or anyone else will be charged in the case.

The arrests of the two women coincided with a federal restraining order against them and 11 others, barring their entry into Ayudando offices at 1400 Central SE without prior approval from the U.S. Marshals Service. Several of those are believed to be family members of Sharon Moore or Susan Harris.

“Based on the widespread indications of criminal activity, centered around Ayudando’s core bank accounts and affecting all categories of its clients, it appears Ayudando is permeated by criminal activity,” said one IRS agent in seeking a July 12 search of Ayudando offices. “Efforts to restrict the search to certain client files would be futile and could result in substantial under-collection of evidence of criminal activity.”

Federal agents who executed the search removed more than 476 boxes of documents along with computer hard drives from the business.

Accidental discoveries

The affidavits chronicle how over the past year at least four employees, referred to as confidential witnesses, came forward with information about the alleged embezzlement. The affidavit refers to them as “walk-ins.”

They told federal investigators how they discovered that Ayudando client funds were disappearing. At least twice, according to one affidavit, the employees found out by happenstance while company owners appeared to take steps to keep their activities hidden.

For instance, the affidavits say:

⋄ One employee accidentally wrote a check for client services from a client’s Veterans Affairs money market account. The check bounced, and, when she called the bank, she was told the money market account had been closed due to insufficient funds. According to the bank, there had been about $100,000 in transfers from the client’s VA money market account into other Ayudando bank accounts.

⋄ Employees who work as representative payees – managing monthly client pension or benefits checks from the VA or Social Security – didn’t normally have access to Ayudando petty cash account. But several months ago, an employee accidentally got access to that account “and saw that there were lots of payments from the petty cash account to the Ayudando owners and their family members. There was also a $75,000 payment to an American Express card from the petty cash.”

⋄ At least two confidential witnesses reported that their prior access to VA clients’ savings or money market accounts had been taken away several years ago. That kept them from seeing the balances. They had access only to a client’s checking accounts.

⋄ One employee alleged that she had a client who died about four or five years ago and who was missing about $30,000 from his account. The confidential witness told investigators the deceased client had money “that should have been returned to Social Security.” After she asked defendant Moore if the funds had been returned, the employee “lost access to that client’s account, and doesn’t know if the money was ever returned.”

⋄ One relative of Ayudando president Susan Harris who works as a guardian is alleged to have taken about $22,000 in client funds from two different clients and failed to provide receipts to show where the money went. Such client advances require that guardians submit receipts. When informed about the issue, Moore told the employee in charge of the accounts that she would “take care of it.”

Stealing from veterans

The indictment singles out the cases of 10 veterans the government contends were victims of the alleged embezzlement scheme. Information in the affidavits suggests there could be several dozen more clients whose accounts were illegally tapped.

For instance, one employee told federal agents that one developmentally disabled client was missing about $30,000 from his account.

Another employee discovered on Jan. 24 of this year that 25 clients were missing a total of about $70,000 from their accounts.

Still another employee told investigators “that she deals with mostly Social Security income clients who have limited income and financial resources. She stated that “she has some clients who are children that are missing money.”

The indictment alleged that the defendants diverted more than $4 million from petty cash and client reimbursement accounts to pay off credit cards used to pay for luxury vacations, vehicles and more.

The July 12 search warrant affidavit also stated, “Additional large, unusual and questionable checks were written to pay for additional items that do not appear to be related to client accounts.”

Missing private cash

“Guardianship/Conservatorship services may be needed when someone is incompetent to manage his or her own financial affairs and/or personal care, and has no viable alternative method of delegating these duties to another,” the company web site states.

About 166 of Ayudando’s clients in New Mexico receive such state-funded services, because they were deemed indigent or met other eligibility requirements. The company also had dozens of “private pay” accounts, according to court records.

The affidavits allege that more than $1 million was missing from at least eight “private pay” client accounts. An employee, referred to as confidential witness #2, was responsible for managing Ayudando’s client bank accounts, paying client bills, selling client assets such as real property and automobiles, and attending court as part of the conservatorship process.

That employee alleged that Moore, the chief financial officer, allegedly took about $700,000 from one client’s estate. The estate was supposed to be settled in February 2017 and the employee became concerned that “it wouldn’t be possible to close the estate if there was money missing.” She said Moore recently returned about $220,000 to the estate, but the money came from four other client bank accounts. Another $500,000 was still missing, the employee reported to federal agents.

—-

To read this article on the Albuquerque Journal’s website, please click here.