Florida: More on investigation into Judge Colin’s wife & guardian Betsy Savitt

From the Palm Beach Post:

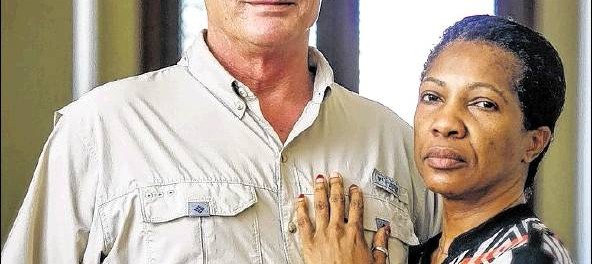

Carla Simmonds, a Delray Beach nursing administrator and mother of two, decided two years ago to get in shape by attending a “boot camp workout.”

But after a vigorous session in February 2014, Simmonds suffered a life-shattering stroke caused by a leak in her carotid artery that triggered a massive blood clot in her frontal lobe. Doctors were forced to temporarily remove half of the 47-year-old’s skull to contain swelling so her brain did not dislodge from her spinal cord.

Simmonds was left unable to speak and with the mental capacity of a 4-year-old. All she could do was cry. Years of recovery awaited.

Daniel Schmidt, a former boyfriend and retired Merrill Lynch financial planner, stepped up, taking her into his home and guiding her on a remarkable recovery.

But the court system also ended up putting the stroke victim in the hands of professional guardian Elizabeth “Betsy” Savitt, the wife of embattled Palm Beach County Circuit Judge Martin Colin.

The judicial power couple were the subject of a series of reforms handed down this year by the chief judge after The Palm Beach Post’s series, Guardianships: A Broken Trust. The newspaper’s investigation showed how Savitt took tens of thousands of dollars in fees without prior court permission from seniors in her guardianships and compiled a litany of complaints from families of her wards.

All of Savitt’s guardianship cases were moved to the north county courthouse to avoid any appearance of favoritism toward the judge’s wife.

Savitt, though, is still drawing complaints about her fees in the handful of guardianship cases she has left. When families ask her to resign, she has demanded fees upfront for her and her attorney Ellen Morris. The judge’s wife insists they also agree not to sue or pursue litigation against her.

‘All about the money’

In the Simmonds case, Savitt, a former tennis pro, attempted to draw fees from the stroke victim’s $640,000 trust, which wasn’t part of the guardianship money, and then wanted to drain her $46,000 IRA to pay fees for about one-quarter of its worth.

But Schmidt stood in Savitt’s way. Simmonds before her stroke had given him her power of attorney.

“From the outset, whether it be her family, the lawyers or the guardian, nobody has acted in Carla’s best interest but me. It’s been all about the money,” Schmidt told The Post.

In order to get Savitt to resign, Schmidt opened up his own wallet and wrote a $9,000 check to Morris. He wrote another check from Simmonds’ trust account for $4,300 for Savitt’s fees.

“I said, ‘Enough! Eliminate these people — stop the nonsense,’” Schmidt said. “It’s amazing how you got to fight all these people. And it all goes against the person who is supposed to be protected: Carla Simmonds.”

In another case, Susan Bach is trying to finalize as well Savitt’s resignation as the guardian of her father, 86-year-old Albert Bach. He has been in a Connecticut nursing home near her since December, but his daughter has been wrangling with the judge’s wife and her attorney for months.

Susan Bach had to consent not to fight Savitt’s fees in court if she wanted the judge’s wife to resign.

“We can’t get rid of Elizabeth Savitt. My father keeps asking me, ‘Is she gone yet?’ because he can’t stand her,” she said.

“I think she gets away with things normal people wouldn’t be able to get away with. I feel like a rabbit in a rabbit hole who can’t get out because people keep throwing dirt on you.”

Fernando Gutierrez, a current board member for the Florida State Guardianship Association, said he would never demand fees upfront if asked to resign from a case.

“We are talking about human beings here and I think her approach is inhumane,” he said. “She should show a little mercy.”

He said guardians like Savitt give the profession a horrible image.

“The fact is she has already been paid some money and she is holding these people hostage. It’s almost barbaric,” he said. “This is really, really bad.”

‘Higher standards of best practices’

When it comes to billing practices of professional guardians, Chief Judge Jeffrey Colbath has vowed to standardize the process. He appointed a committee of circuit judges John Phillips, Janis Keyser and Jessica Tick-tin to look at guardianship not only within the courts, but among lawyers, guardians and other stakeholders.

“Based upon our ongoing examination of how guardianships are handled here and around the State, we have discovered that the practices vary widely,” Col-bath said. “We here in Palm Beach County strive not only to meet the legal requirements imposed by law and rules of procedure, but to achieve a higher standard of best practices.”

Families in other Savitt guardianships have leveled complaints about doubled-billing and the judge’s wife pursuing unnecessary litigation that increases fees for herself and her attorneys.

Savitt contends she isn’t the only guardian who takes fees before judicial approval and has the blessing of her attorney, Morris, the administrative chair on the Florida Bar’s executive Committee of the Elder Law Section.

The auditor for the Clerk and Comptroller’s Office, which reviews guardianship cases, told The Post for the January series that the judge’s wife was the only guardian in the county to take fees without prior court approval.

Fees take center stage in the contentious Simmonds guardianship, fueling the tell-tale acrimony found in many of Savitt’s cases.

Documents show Savitt and Morri s initially attempted to pry open Simmonds’ $640,000 trust for fees despite the fact that they knew the trust was off limits to the guardianship, according to pleadings. When Schmidt objected, the duo dropped the matter and moved on to Simmonds’ $46,000 IRA.

The judge’s wife described Schmidt — as she has done her other critics — as “disgruntled.”

“His contentions are not worthy of response,” Savitt wrote in an email to The Post.

Morris said Schmidt has not allowed Simmonds to see her family. She said he uses vulgar language, makes threats and that she has “proof of the poor character of this man.”

“I cannot fathom except to continue sensationalizing a non-story for your own gain to the detriment of innocent people,” she said in her email.

Morris, in an April 20 email to Schmidt’s attorney, demanded he retract statements to The Post.

“If an article is published, Betsy will have to respond by publishing your client’s texts and emails,” Morris wrote. “And if we go to hearing I will (be) introducing those texts and emails into the record for the judge to hear.”

Schmidt echoed concerns of other families, saying Savitt appeared over her head in handling Simmonds’ finances.

Among his complaints are that the judge’s wife bungled Simmonds’ finances, mistakenly saying she owed income and property tax when she didn’t. Savitt also failed to secure insurance in order to rent out the stroke victim’s empty Delray Beach residence, he said.

The retiree says he has spent $150,000 of his own money on Simmonds care and legal fees. He lost an effort to sell Simmonds’ 2013 Honda Civic, worth an estimated $15,000, when Savitt — with a judge’s consent — gave it to the stroke victim’s eldest son.

In the Bach case, when his daughter asked about fees, Savitt unleashed an email tirade, threatening to bring up accusations against Susan Bach in court.

“You should present that matter to the judge to see if he agrees with you,” Savitt wrote Susan Bach on May 11. “If you do not take that action, it will be clear that you are continuing to bark frivolous claims that cast unfavorable light on you.”

Schmidt said an angry Savitt has shown up unannounced on his doorstep more than once making the unsubstantiated allegation that he was abusing Simmonds and that she was going to put the stroke victim in a nursing home.

“Throughout this entire time, I’m being threatened,” Schmidt said. “She said, ‘My husband is a judge. You don’t know who I am. I can get away with anything I want in court.’ ”

Morr i s said Savitt i s “court-ordered to visit her ward. She has the right to show up announced or unannounced at any time.”

She says Savitt would never threaten her ward or put Simmonds in a nursing home.

‘Scared to death’

But Simmonds has recovered enough that she can speak in one- or two-word sentences. Her sunny disposition shines through on the daywhenshewasinterviewed.

When asked: “If you could say one word how you feel about Elizabeth Savitt what would it be?”

“Ooh. Bad. Bad. Bad,” Simmonds responds.

“Is she not nice to you?” Simmonds is asked.

“No. Threatening,” the stroke victim manages to say.

When asked what the threats were, Simmonds struggles but manages to say: “Nursing home.”

Schmidt said that Simmonds ended up in tears after speaking to Savitt on the phone in February 2015. “To this day, Carla is scared to death of Savitt,” he said.

Court-ordered guardianship is designed to protect the well-being and finances of incapacitated adults. Most of the time family members serve as guardians, but in about one-fourth of the cases, professional guardians such as Savitt are appointed by judges.

The state Legislature has tried to rein in the industry after receiving numerous reports of abuse, passing reforms to give the state more authority over guardians and to hold them criminally accountable if they are abusive. But, more often than not, families and loved ones of the ward are left to fight their own battles in front of judges, footing the bill for their own attorneys.

After Schmidt’s lawyer filed an objection, Circuit Judge Karen Miller wouldn’t immediately sign off on liquidating Simmonds’ IRA and encouraged a deposition of Savitt about the issue and other disagreements.

But Judge Miller recused herself for reasons unknown in both the Simmonds and Bach cases.

In the Bach guardianship, the ward’s daughter has been trying to get a judge to sign off on Savitt’s resignation for nearly four months since she moved him to Connecticut in December. Susan Bach said she felt pressured to sign a settlement agreement to pay Savitt and Morris their fees.

“They said if I didn’t sign it and it went to a court hearing, they could still take more money from dad and then he would be penniless. They could take money for phone calls, for emails, court costs,” she said. “I am stuck. I have no leverage. She has my father’s money. He only has $25,000 of his life savings left and they want to take as much as possible.”

Frustrated, Susan Bach secured a court hearing set for Friday, May 27.

‘Crucial issues’

In the Simmonds case, Morris urged Judge Miller at a March 23 hearing not to delay liquidating the $46,000 IRA and paying her fees: “We need to proceed your honor, because these are crucial issues,” she said.

But Morris had received some money for her work. Records show that Savitt paid attorney Morris at least a half dozen times about $6,000 total from the Simmonds guardianship. When asked about the payments before judicial approval, Morris said they are allowed under state guardianship law. “Correct fact but so what?” she wrote in an email reply.

David Garten, Simmonds’ attorney who is paid by Schmidt, said Savitt and Morris’ desire to liquidate the IRA account to pay for a few thousand dollars in fees wasn’t in the best interest of the stroke victim.

“So you are owed about $6,000? Why do you want to take the client’s retirement account, cash it in, and get 50 cents on a dollar after taxes and penalties?” Garten told The Post. “We were trying to understand what their logic is there.”

Savitt and Morris had other venues to draw their fees: $3,300 in the guardianship account, $1,500 a month from Social Security, $2,800 in Simmonds’ health savings account and $5,000 owed from health insurance, according to court documents.

Garten said Schmidt has dedicated years of his retirementtakingcareofSimmonds 24hoursaday—somethingno nursing home or hired caregiver would do. “He is giving her the best of care,” he said.

Schmidt never imagined himself in his current situation. He had lost touch with Simmonds after they briefly dated, but got a call from her attorney after the stroke. He found out that he had her power of attorney over the $640,000 trust and had been namedherpersonalrepresentative in case she died. He said he was reluctant to sign on but was persuaded by the family.

He said Simmonds obviously had good reason to protect her assets: “She knew her family better than I did.”

When Schmidt sought to be Simmonds’ permanent guardian, he ran into opposition from the family and by the stroke victim’s court-appointed attorney at the time. Savitt then entered the picture, appointed by Judge Jeffrey Gillen, who then worked a few doors down from her husband.

Despite his negative experience, Schmidt still has faith in the guardianship system.

“I have to believe there are people who know what they are doing and they do give a little empathy back toward the ward,” he said “There has to be people out there who don’t threaten people to get their way. And they do sit down and try to understand the facts and work for the best interests of the ward and not for themselves.”